Foodservice, the role of “Public Food,” and the rise of McDonald’s

A Part 1 introduction to a multi-part series

In Foodservice to Family

This topic is personal for me in a couple different ways.

From 2016 to 2020, I served on the board of the Sons of the Revolution in New York and remain a member of the organization today. We own Fraunces Tavern — the oldest restaurant in New York City and, depending on how you define it, the oldest surviving structure in Manhattan. The core of the building was put up in 1719 as a private home for the De Lancey family — Huguenots who fled persecution in France— and was later converted into a tavern by Samuel Fraunces in 1762. Over the years, it went by names like Queen Charlotte Tavern, Queen’s Head, Boltons Tavern, and The Coffee House, but quickly became one of the key watering holes of colonial New York… a meeting place for the Sons of Liberty, a venue for early commercial and political life, and eventually a headquarters for George Washington himself.

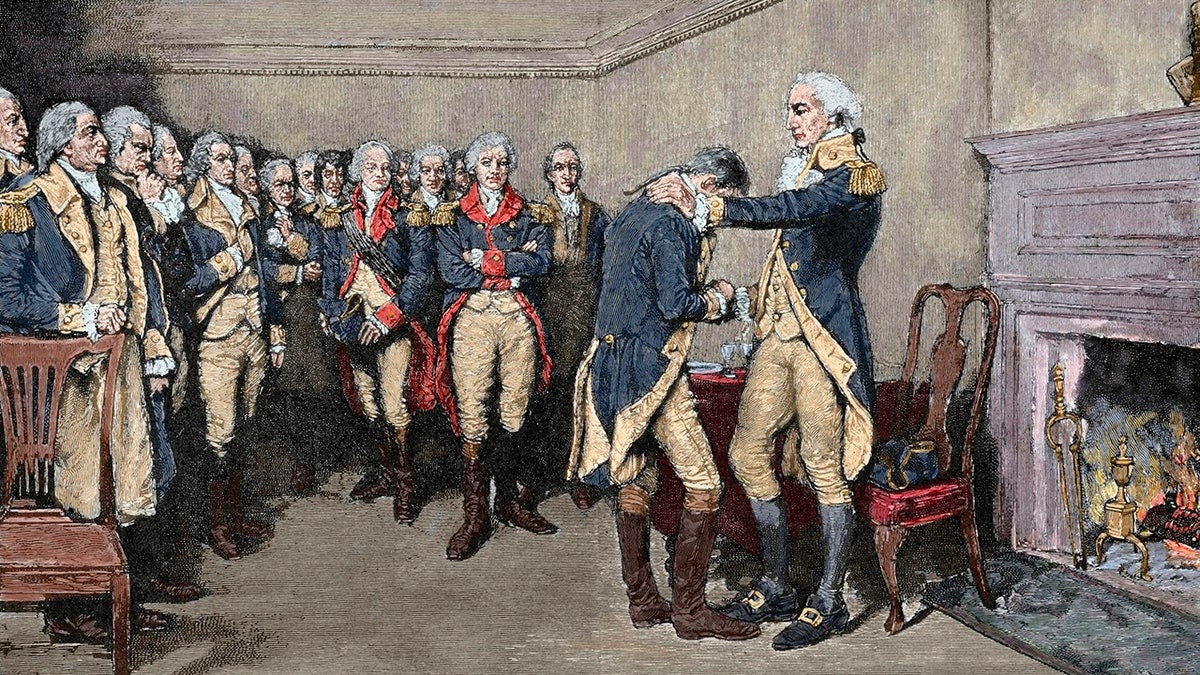

Fraunces is where Washington hosted his famous farewell dinner for his officers on December 4, 1783 — nine days after the last British troops left New York. It later housed early federal offices under the Articles of Confederation, then survived fires, near-demolition, and a 20th-century reconstruction before landing in its current role as a museum and tavern. Today, you can still walk up the narrow stairs, duck your head under the beams, and drink a beer in rooms where people once argued about tea, empire, slavery, and what exactly this “United States” thing was going to be.

In my late 20s and early 30s, when I was working in Manhattan, Fraunces Tavern became one of my unofficial offices. I spent a lot of time there — board meetings upstairs, drinks downstairs after work, wandering through the museum rooms in between. My family on my mother’s side has roots that run deep into that early American story… back to Concord, MA and to the Mayflower. I’ve always been drawn to that era, and the evolution of American life from those tavern rooms to the modern system fascinates me. That’s a big part of why I got involved with Sons of the Revolution in the first place.

But the other half of the story sits on my father’s side, and it’s very German and very food-centric. For that branch of our family, the food and restaurant business was one of the main ways they solidified their standing in America — first in New York City, then across the river in Jersey City and Hoboken in the late 1800s and early 1900s. My grandfather’s grandfather, Charles Lehmann, was born in Saxony in 1845 and came to the US with his parents, also born in Saxony, at around age six or seven. He married Franziska Spillner (later anglicized to Frances), who was born in Berlin, the capital of Prussia at the time, and likewise came to the US as a young girl. Frances’ father was born in Hanover and her mother in Mecklenburg. The two of them met and married in Manhattan in 1867, then moved to Jersey City, New Jersey — which, at the time, was a major German immigrant hub.

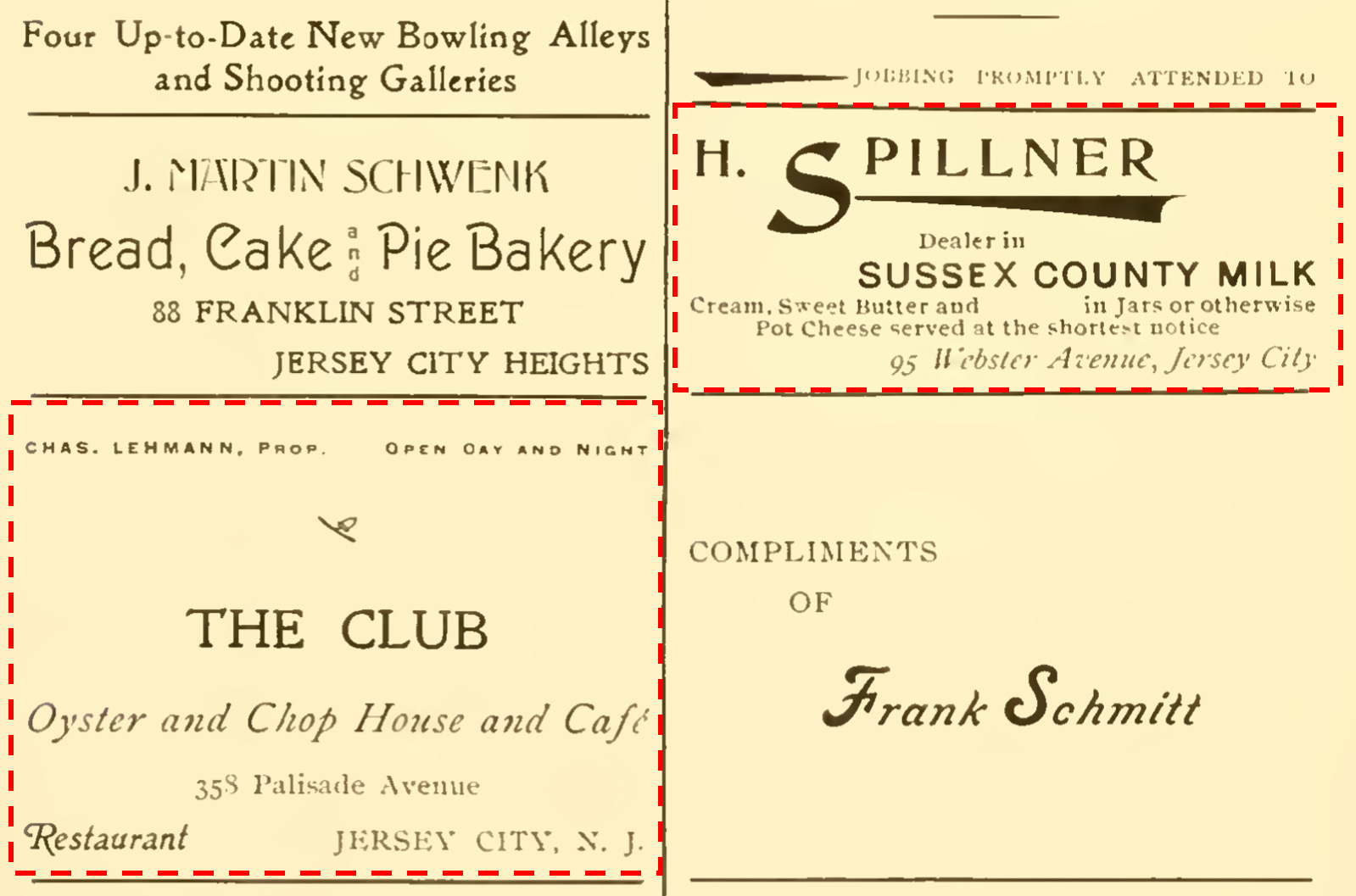

It’s hard to picture now, but the entire Jersey City Heights area that people know today was once a center of German culture in America, where everyone spoke German. It had German schools, German clubs, and Turnverein societies — the Turners’ movement of gymnastics, civic life, and culture transplanted onto American soil. One of the beautiful surviving artifacts of that world is a book called Zur Feier des Fünfzigjährigen Jubiläums der Hudson City Turn Vereins, 1854–1904: 23–27 November, 1904, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Hudson City Turn Verein. In that volume, two small advertisements sit diagonally across from each other. One is for Charles Lehmann’s restaurant — “The Club” Oyster and Chop House and Café. The other is for the Spillner family’s milk dealer business. On one page, you can literally see both sides of my father’s line in the food economy of that neighborhood… restaurant on one side, supplier on the other.

So, my father’s side were originally food suppliers and restaurateurs. Which makes it feel at least somewhat poetic that I was eventually drawn into the world of consumer goods, and that I ended up covering the food and restaurant sector on Wall Street for several years.

It’s also beautiful and inspiring to trace how that world actually came into being for my family. When you follow the early US census records, you can watch Charles Lehmann’s life evolve decade by decade. In his 20s, he’s listed simply as a “laundry man,” doing the kind of hard, low-margin labor that defined immigrant life in the 1860s and 1870s. Then, across later censuses, the description shifts to “own income,” which in that era was census shorthand for being a business owner, a proprietor, an entrepreneur. Someone who wasn’t taking orders anymore.

That shift — from doing the washing for other people to owning a restaurant in a German-American enclave — is the exact American story. The upward climb, the self-made pivot, the gradual acquisition of dignity, autonomy, and standing in a an entirely new country... a new continent.

And so this preserved advertisement feels mythic to me. To have a surviving print ad for The Club — Charles Lehmann’s place — sitting in that Turn Verein commemorative book across from the Spillner family’s milk-dealer advertisement is like holding a tiny piece of American economic history in my hands.

When I study the foodservice sector, I’m really looking at the soil my family was planted in… the system they fed and that fed them… and ultimately shaped the circumstances of my own existence.

Reintroducing the Industry Frame

As with our previous two pieces, this installment will weave the story of a single company with the story of the industry that shaped it.

In the Walmart piece, we examined the rise of modern retailing: centralization, scale, store economics, and the strange, esoteric world of trade-promotion spending — and how Walmart both influenced and was influenced by those forces.

In the Cargill piece, we had to lay down the geopolitical and agricultural realities that made a company like Cargill not just possible but inevitable.

We’ll do the same with McDonald’s. Because before McDonald’s can be understood as a business or a brand, you have to understand American and even global foodservice itself — its conceptual and practical origins — and the centuries of evolution that led up to the mid-20th century moment when McDonald’s appeared on the scene. McDonald’s emerged as the logical product of centuries of American eating patterns, labor structures, and technological change — and then amplified those patterns, standardized them, and exported them to the world.