The Invisible Empire: Cargill (Part 2)

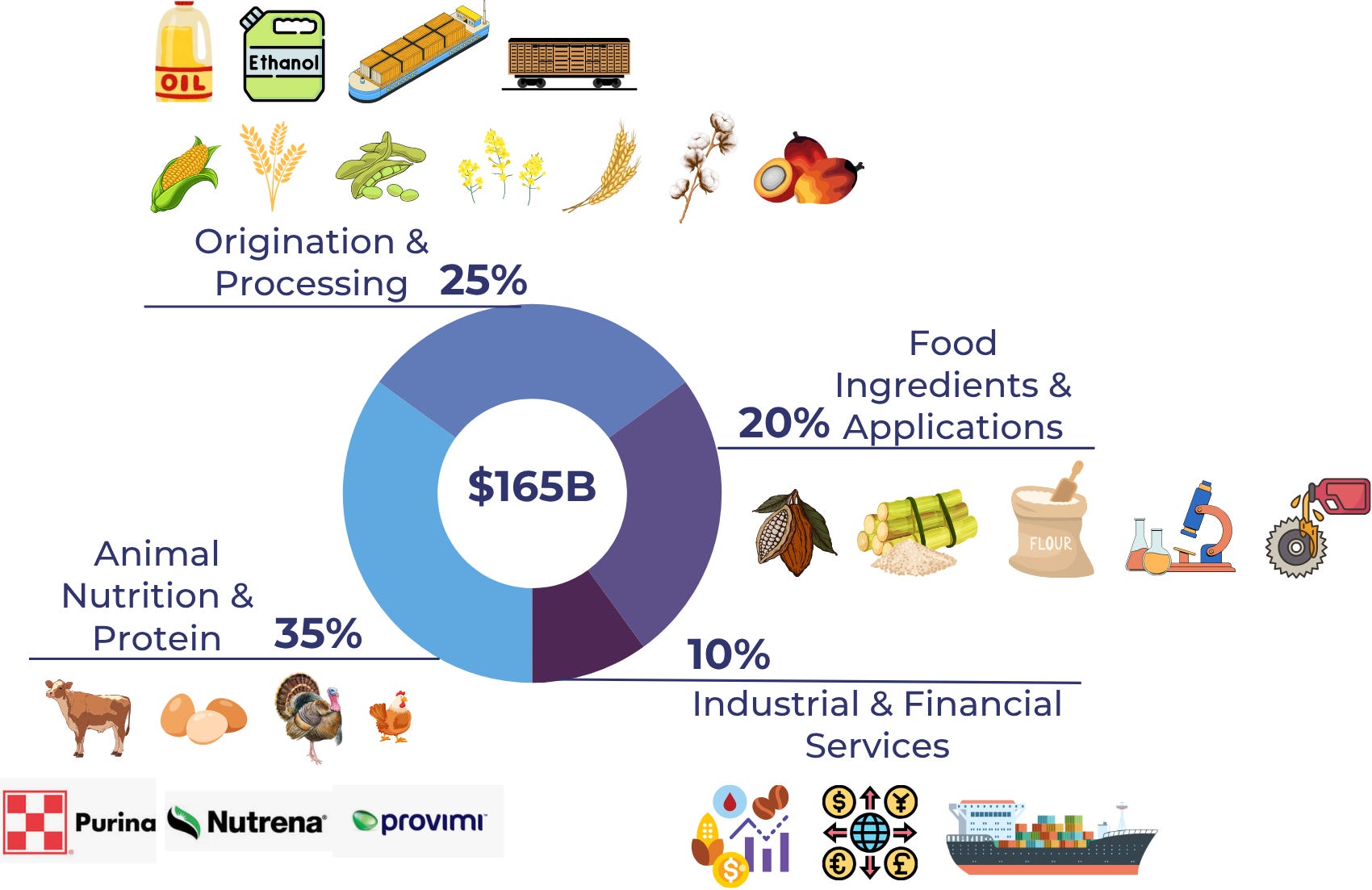

In June, we previewed this deep dive into Cargill, the largest privately held company in the United States (by revenue, latest available figure ~$165 billion FY 2022) and one of the most influential agricultural merchants — merchants of any kind, really — in the world. But before diving into the company itself, we had to explain the geopolitics and agricultural uniqueness of the US — and why a firm like Cargill was inevitable.

Now, let’s turn to the company itself.

Catching up on 160 years of history

Cargill was founded in 1865 when William Wallace Cargill purchased a grain warehouse in Conover, Iowa. Over the following decades, the Cargill family expanded along railroad networks, acquiring grain elevators, warehouses, and other storage assets across the Midwest. In essence, Cargill began by providing a critical service to the nation’s farmers — connecting them to domestic and world markets. As we explained in Part 1, individual farms lack the capital, infrastructure, and scale to handle their own distribution, so companies like Cargill step in to buy crops locally, store them, and move them efficiently to transport or export hubs where they can be sold elsewhere or abroad.

In 1904, William’s son-in-law, John MacMillan, joined the business. This marked the beginning of the Cargill–MacMillan family partnership, which endures to this day. Both families remain the principal shareholders, making Cargill one of the largest privately owned companies in the world. (There’s no public float — ownership is split among dozens of heirs, many of whom are billionaires on paper.) Over the next century, Cargill expanded far beyond grain storage and transport, acquiring companies and assets that added new services and business lines — from meatpacking and animal nutrition to cocoa processing, ocean freight, and even financial services and commodity risk management. The logic was straightforward — by building out capabilities across every stage of the agricultural supply chain, Cargill could both capture more margin and reduce its dependence on any single commodity, region, or market cycle.

But for most of its existence, Cargill has operated largely outside public view — a deliberate strategy made easier by its private status. But that changed somewhat in 1972 during the so-called “Great Grain Robbery” when the Soviet Union, suffering a poor harvest, quietly purchased millions of roughly 10 million tons of US grain at relatively low prices. Cargill, like other major American grain traders, sold large volumes to the Soviet grain-buying agency Exportkhleb — unaware that the Soviets were making similar deals with multiple other firms at the same time. This fragmented buying concealed the total size of the purchases from the market, US officials, and the traders themselves until the deals were complete. When the cumulative purchases came to light, domestic grain reserves had already been depleted, and prices spiked for US businesses and consumers. Worse, US taxpayers ended up effectively subsidizing Soviet purchases through existing export credit programs. The controversy marked the first time many Americans had ever even heard Cargill’s name… and the first time the company’s global role came under any real public scrutiny or political pressure.

The public backlash — especially amid rising food prices at home — led Congress and the USDA to overhaul agricultural export reporting. The most notable resulting change was the creation of the USDA’s Export Sales Reporting Program in 1973. This policy required US exporters to promptly report large foreign sales of major commodities to the USDA, which would then publish the data on a weekly basis. The goal was to give both the government and the market visibility into large export deals to avoid being blindsided again. This reporting requirement still exists today and is considered one of the more lasting regulatory changes in global grain trade transparency.

Food industry classic Merchants of Grain, written in 1979 by Dan Morgan, was the first major book to dive head first into Cargill’s world — and the Russian grain “robbery” is prominently featured (there was a book called The Great Grain Robbery written in 1975 by James Trager that went into even more detail). Morgan goes on to reveal how Cargill was (and remains) part of a small, secretive group of global grain traders (often referred to as the “ABCD” firms — ADM, Bunge, Cargill, Louis Dreyfus). Morgan explained how Cargill’s reach extended from US farms to ports, to international shipping lanes, to foreign mills and buyers… showing how a handful of companies quietly mediated global food flows far beyond day-to-day scrutiny let alone awareness. More recently, The World for Sale written in 2021 by Javier Blas and Jack Farchy revisited Cargill in the broader context of global commodity trading (i.e. not just food) — still largely private, still low-profile, but wielding enormous influence over supply chains that governments and populations depend on.

Today, Cargill is more likely to appear in investigative or activist journalism than in mainstream business headlines — and often in a negative light. The company has been criticized for its role in Amazon deforestation linked to soy and beef supply chains, child labor concerns in West African cocoa sourcing, and environmental damage from palm oil operations in Southeast Asia. Whether these issues stem from direct operations or from suppliers, they’ve put Cargill at the center of debates over environmental responsibility in the global food system. And this criticism is also inevitable given the unprecedented size of the company and its sprawling everywhere-at-once operations around the world.

The Business(es)

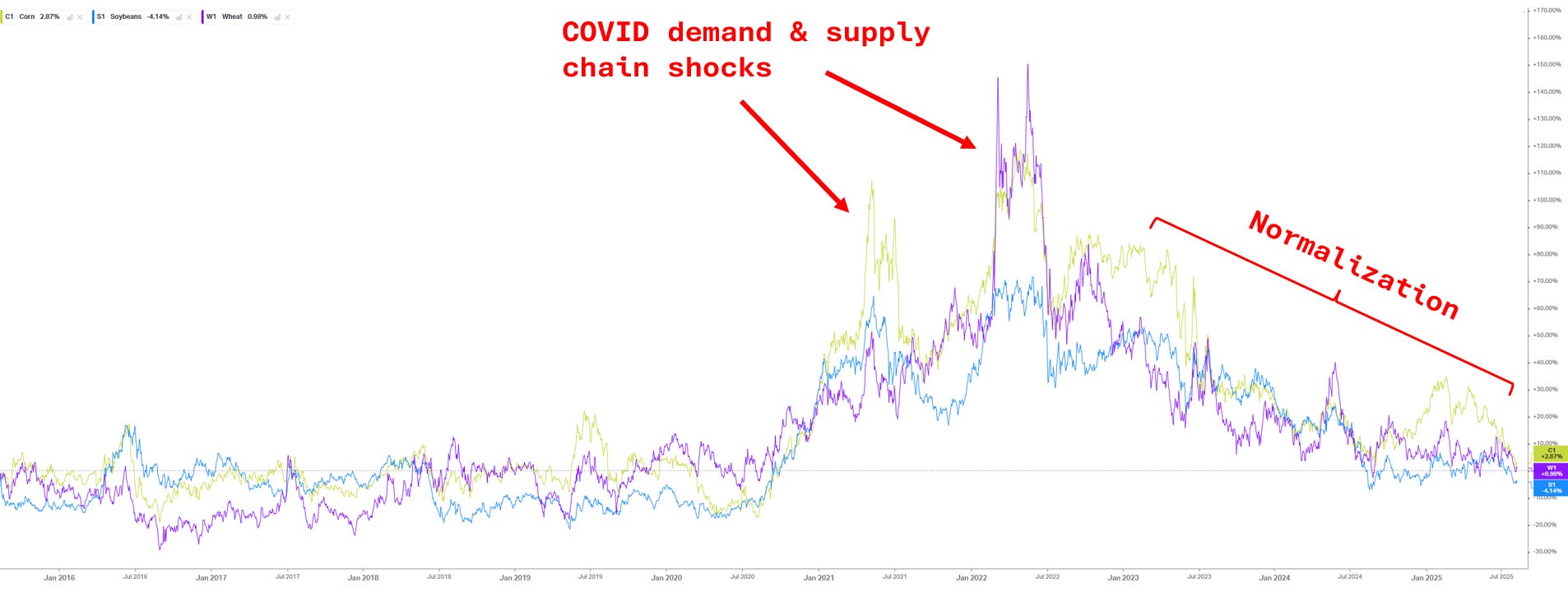

Cargill announced late last year that it would restructure its operations after falling short of its own profit targets — which were largely driven by the normalization of grain prices (which compresses margins) in recent years following the rapid demand (e.g. animal feed for higher meat demand) and supply chain-driven (e.g. labor shortages, Brazil drought) price spikes during the COVID years. The company said it would streamline its business segmentation from five units to just three. But let’s take a look at its pre-2025 organization (thanks to a 2023 bond prospectus we dug up) to get the best understanding of the business.

Let’s go…