Understanding US Population Projections

There's too much online prognostication and too little data analysis. Let's set the record straight on what's happening.

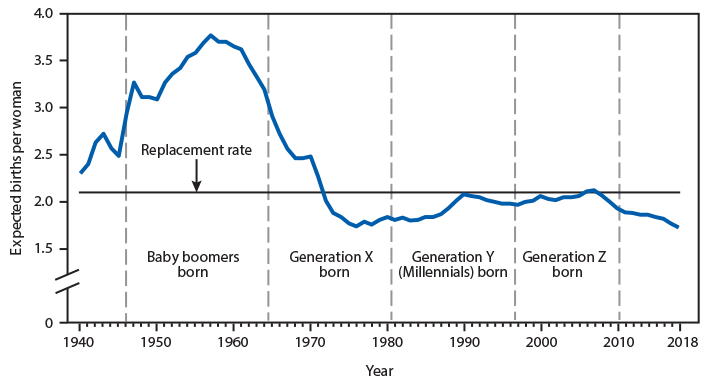

After World War II, thanks to soldiers returning home, a booming economy with jobs for everyone, and new government support (e.g. the GI Bill, subsidized low-interest mortgages, and family-friendly tax benefits), the US fertility rate soared to a peak of about 3.8 in 1957 and stayed in the mid-3s from the mid-1950s through the early 1960s before steeply declining after 1964 and falling back toward the longer-term modern norm of roughly 2.0–2.1 (the “replacement” level for a stable population).

It’s important to understand that this was an unusually large and historically specific spike fueled by stability and prosperity after years of pain and hardship. The US was effectively the only major industrial economy left intact, while Europe and Asia were rebuilding from the ruins of war, so American factories and farms exploded with demand, creating the perfect storm for large families and rapid population growth.

But this created an artificial ripple in birth patterns, like dropping a huge rock into a lake. It created these neat, somewhat “artificial” generational silos we now call:

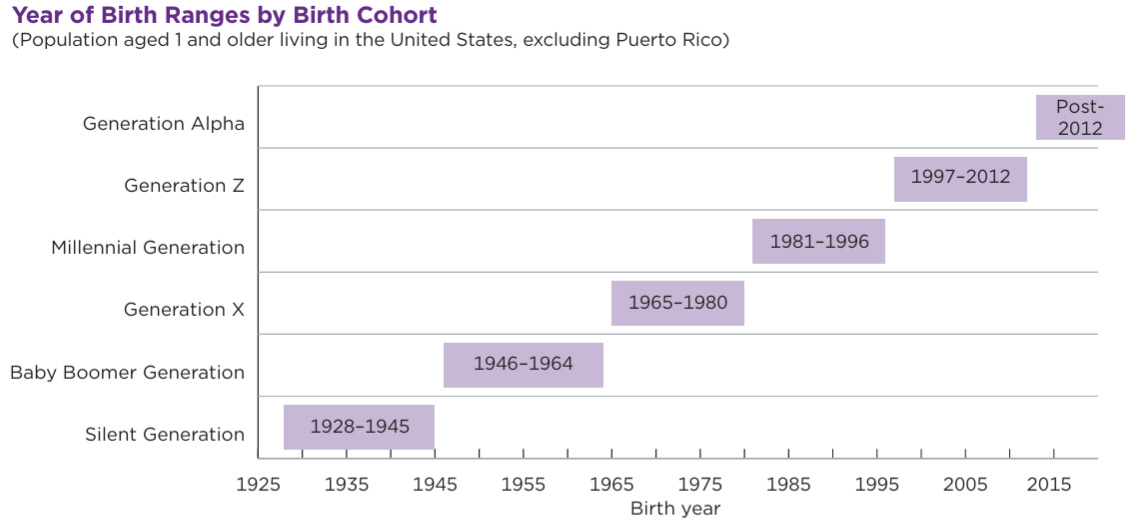

Baby Boomers (born 1946–1964)

~76 million births

Gen X (1965–1980)

~55 million births

+ modestly boosted by post-1965 immigration

Millennials (1981–1996)

~62 million births

+ boosted by ~10 million due to heavy immigration and the children of immigrant families

Gen Z (1997–2012)

~69 million births

+ modest boost by immigration

Gen Alpha (roughly 2010s to mid-2020s)

~40 million in the US so far and growing

So the Boomers were the children of the returning WWII generation, the first ripple. Since the Boomers were an unusually large cohort, their children — mostly Millennials — were also large in absolute numbers even as fertility rates declined. In turn, Millennials’ children (Gen Alpha) form a third ripple, though weaker, because fertility rates have continued to trend downward over time… a normal expectation as countries grow richer, more urban, more educated, etc.

This meant the generations immediately before and after the primary “ripple” would appear smaller by comparison, as they reflected a more “normal” fertility environment rather than one supercharged by postwar conditions.

But nothing is ever “normal,” is it?

As the US fertility rate was otherwise returning to “normal,” it suddenly collapsed in the early-to-mid 1970s and remained depressed through the early 1980s. This was driven by a whole host of factors: the 1970’s oil crisis and stagflation, economic uncertainty and recessions, women’s liberation and rising workforce participation, widespread availability of birth control, and the legalization of abortion through Roe v. Wade. This is the chaotic period produced Gen X, which at roughly 55 million births became a true demographic “trough” following the Boomer peak of 76 million.

Then, from the late 1980s through the mid-2000s, the fertility rate stabilized near replacement, generally hovering around 2.0–2.1, with most years right at or slightly above 2.0. The driving factors now were Reagan and Clinton-era economic growth and delayed but more planned (and smaller) childbearing amid a surge in white-collar professionalism, college graduates, etc. As a result, Millennials became the largest generation by total population with ~72 million people in 2019, surpassing the then-size of the Boomers.

Gen Z is also large at roughly 68–69 million, but smaller than Millennials — and would likely be smaller still were it not for decades of sustained immigration following the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act. Immigration both increased the size of the Millennial and Gen Z cohorts directly and boosted birth totals through the children of immigrant families, muting what would otherwise have been a sharper demographic “trough” as the children of the smaller Gen X.

Then came the next shock

The Great Recession collapsed the fertility rate from about 2.1 in 2007 to the high-1.8s by the mid-2010s and into the low-1.7s by 2018. This occurred just as early Millennials were entering adulthood and late Gen Z were being born. Net immigration also slowed because of the economic crisis. The fertility rate never truly recovered and now sits around 1.6 — among the lowest levels in US history, comparable to or below the 1970s collapse.

The crazy “what if” is that the fertility rate may have partially rebounded as Millennials regained stability… but just as they entered prime family-formation years, COVID arrived, layering new economic and psychological uncertainty onto an already fragile situation. It also created a visible schism within the Millennial generation itself… earlier Millennials, a little further along in their careers and often already homeowners before 2020, experienced a far more stable arc of family formation and wealth accumulation than later Millennials and Gen Z, who entered adulthood amid rapidly rising housing costs, debt and post-COVID social dysfunction that has been well documented. The result may be higher fertility among early Millennials and much lower fertility among younger cohorts, blending into today’s subdued national rate… although this is just me speculating since the data doesn’t cut in that granularity to my knowledge.

This period does not represent the first sustained stretch of sub-replacement fertility (the US has been below replacement most years since 1971), but it arguably represents one of the deepest and most prolonged modern low-fertility eras in both intensity and duration.

Which brings us to the 2050 population projection chart

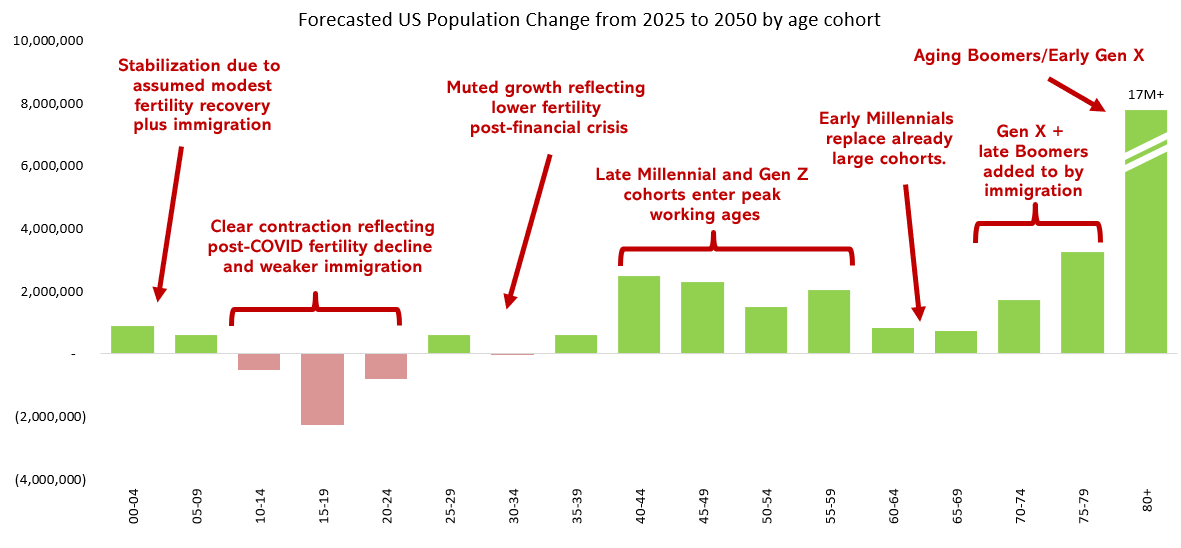

The most dramatic feature is the massive surge in the 80+ population — more than 17 million additional people. This reflects the combined impact of the Baby Boom generation and early Gen X aging into very old age, supported by rising longevity and survival rates that far exceed anything seen in prior eras. This is the clearest expression of America’s rapid demographic aging and the long tail of the postwar population shock.

Just to the left, you see strong growth in the 70–74 and 75–79 cohorts. This is Gen X and younger Boomers replacing smaller earlier cohorts at those ages, reinforced by longer lifespans and the cumulative effects of decades of immigration.

Then you see positive growth in the 60–69 cohort, but the increase here is noticeably more subdued. This band will be dominated by early Millennials in 2050, replacing late Boomers and early Gen Xers currently occupying these ages. While early Millennials are large, they are not disproportionately oversized in the same way as the Baby Boom generation, and they are replacing cohorts that were already moderately sized. In other words, this is a demographic handoff from “large” to “slightly larger,” rather than from “small” to “large,” which naturally produces a more muted increase than the dramatic surges seen at older ages.

Meanwhile, the core working-age bands (roughly 40–59) show solid positive growth — noticeably larger than the increase seen in the 60–69 group, though still well below the explosive surge at the very top of the age spectrum. These cohorts consist largely of younger Millennials and older Gen Z aging into peak earning and working years. Their expansion reflects the ripple of the postwar demographic shock combined with sustained immigration.

Now look to the left side of the chart — this is where the structural shift becomes unmistakable and a little scary.

The 10–14, 15–19, and 20–24 cohorts all show net population declines, with the sharpest contraction in the 15–19 bracket. These declines reflect fewer children born during a prolonged period of sustained low fertility that intensified further after COVID. They also capture the secondary impact of disrupted immigration flows — particularly the sharp slowdown during the COVID period and subsequent volatility from shifting immigration policy — which reduced one of the primary stabilizing forces that would otherwise have partially cushioned these cohorts from even steeper decline.

Then the 0–4 and 5–9 cohorts show only slight positive growth — a stabilization rather than a rebound. This is not evidence of a new baby boom, but a demographic floor sustained by continued immigration and a relatively large pool of women of childbearing age, even as fertility remains assumed around ~1.6. In other words, the base is being held up more by demographic momentum and population inflows than by any revival of native birth rates.

So what we’re seeing is the visible unwinding of the Baby Boom.. or the ripple disappearing… as the demographic engine that powered American expansion for two generations ages out of dominance, leaving behind a population structure increasingly defined by longevity and immigration rather than natural replacement.

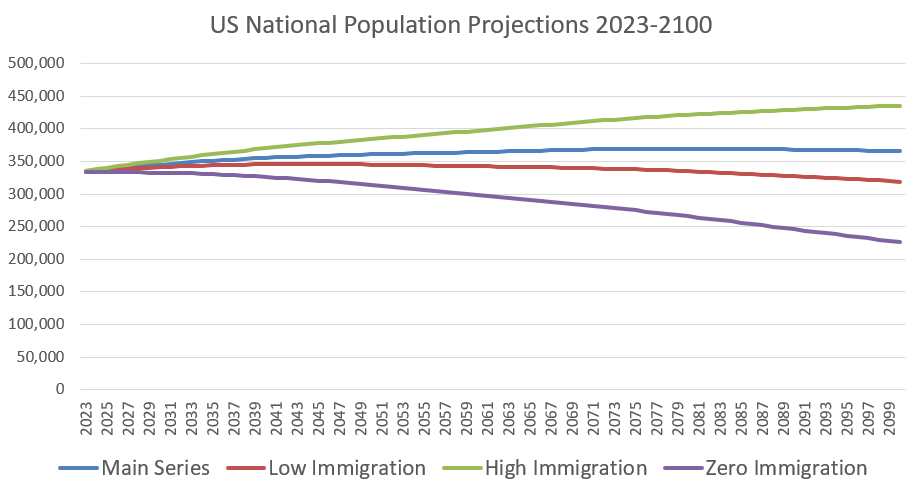

For example, here’s a look at what the US population would look like with zero immigration.

Can you imagine?