One Year Later: Big Food Is Breaking Apart, Just Like We Predicted

Last summer, we laid out a framework across three essays.

In Expect Big Change in Big Food (July 8, 2024), we showed how underwhelming total shareholder returns (TSRs) eventually force boards into radical action. Spin-offs, restructurings, or sales don’t happen just because management think they’d be interesting or exciting. They happen when stock performance deteriorates and boards face activist or potential activist pressure, including hostile M&A. Lag behind long enough and change is inevitable whether it’s welcome or not.

Two weeks later in The Great De-Conglomeration (July 24, 2024), we placed this moment in historical context. Big Food, we argued, was still unwinding decades of conglomeration — when companies collected all sorts of unrelated businesses for internal diversification reasons, encouraged by the management academia of the early- and mid-20th century, only to realize investors could diversify more efficiently on their own partly due to the rise of the mutual fund industry. The new playbook was already visible in that boards had begun narrowing their portfolios, carving off non-core divisions, and moving toward “bigger and fewer” category champions.

Finally, in All Quiet on the Midwestern Front (August 13, 2024), sparked by that weekend M&A chatter, we used Kellogg’s as a case study. Decades of underperformance and hometown ties made Kellogg’s look strategically lost, but its cereal spin had unlocked optionality. Suddenly Kellanova looked like a “mini-Mondelez,” and we contemplated its endgame was either rerating or being taken out — with Mars and Hershey as the logical buyers. Of course, the deal with Mars was announced unsurprisingly the next morning, as reports suggested.

So our argument was this… that TSR deterioration creates boardroom pressure, that de-conglomeration is the ongoing megatrend which will only accelerate, and that more dramatic breakups and M&A would unlock optionality in the hopes of jumpstarting TSR again.

One year later, that’s exactly what’s been happening…

Some quotes from our pieces last year

“We believe activists are likely to come back to Big Food unless even more radical changes come first at these companies.”

“Expect more, likely even bigger changes soon.”

“Subsiding inflation should help mitigate the political blowback of any major shareholder-friendly corporate actions in Big CPG/Food.”

“Should Conagra’s growthier snacks business really live alongside its Healthy Choice and Banquet frozen entrees businesses? How many more pet food businesses will General Mills acquire before that business should live independently? Should an activist revive old talks of merging Mondelez and Frito-Lay? Why should Campbell Soup manage a large snacks business alongside its flagship meals and sauces portfolio?”

Deals, Deals, Deals

Conagra sheds some frozen and grocery brands

Perhaps the clearest validation came from Conagra. Again, we wrote last year that its growthier snacks business hardly made sense alongside things like Banquet or Health Choice frozen dinners. Sure enough, this year, Conagra sold Chef Boyardee to Hometown Food (owned by Brynwood Partners) and divested its Van de Kamp’s and Mrs. Paul’s frozen seafood brands to High Liner. We were spot on thematically. These were not trivial portfolio trims but deliberate steps to shed low-growth distractions and focus on the parts of the business that still resonate with consumers. As such, Conagra remains the poster child for the ongoing Big Food “deconglomeration” we wrote about in detail last year.

We expect more to come and still think an ideal transaction is separating the snacks business from grocery/frozen— potentially merging with another scaled public or private snacking franchise, perhaps Utz Brands. “Bigger and fewer” is the name of the game now, in our view.

Kraft Heinz reportedly dismantling the 3G/Berkshire experiment

Kraft Heinz offers another validation. We stressed that spin-offs are ultimately about giving shareholders the chance to make their own allocation choices when management has proven unable. A report from The Wall Street Journal now suggests Kraft Heinz is preparing to split in two — a higher-growth sauces and condiments company on one side and a slower-growth grocery portfolio on the other. This is precisely the kind of de-conglomeration pressure we predicted would come back to Big Food. And what a come down for 3G and Berkshire’s big plans to optimize and synergize Big Food in the US. Their strategy, while well-intentioned, was a failure. Simply put, they failed because they attempted to reverse the flow of the great megatrend of deconglomeration.

Cereal and candy

The cereal side of Kellogg’s story shows how optionality gets unlocked. When the company spun off WK Kellogg in October 2023, we noted how cereal had been a major drag inside a broader snacks portfolio, but as a standalone, it would be interesting to see how the public markets would treat it since M&A optionality (as either a buyer or a seller) seemed absent. Sure enough, Ferrero announced in July it would acquire WK Kellogg for $3.1 billion. Cereal may be a cash-flow business in decline, but in Ferrero’s hands it complements a confection and indulgence portfolio. After all, most breakfast cereal is closer to sugary candy than a hearty breakfast these days.

The Mars–Kellanova story needs less explanation. Since the announcement, it’s cleared US antitrust review and is progressing through Europe although with a little turbulence. It is the quintessential example of “category-line” consolidation. It’s a family-owned powerhouse doubling down on snacks, not trying to be everything to everyone.

Pepsi and Frito-Lay dominate (just) beverage and snacks.

PepsiCo has played the same logic. We argued that the strongest companies would choose scale in fewer categories rather than sprawling portfolios. Over the past year, PepsiCo bought Siete Foods for roughly $1.2 billion and Poppi, the prebiotic soda brand, for nearly $2 billion. Those two moves highlight the company’s strategic discipline in reinforcing dominance in its only two lanes, snacks and beverages, rather than chasing distracting non-core adjacencies. Perhaps that’s why it’s stock performance is the “least bad” among its major US Big Food peers on the 3-year TSR chart (see below).

Split coffee

Keurig Dr Pepper provides perhaps the most striking validation of our “bigger and fewer” thesis. Just a few days ago, the company struck an $18 billion deal to acquire JDE Peet’s, one of the world’s largest coffee businesses. At the same time, it will be splitting itself into two entities — a global coffee powerhouse and a North American beverages player. Instead of a conglomerate straddling categories, investors will soon own two sharper, more focused category leaders. This again is a stark reversal from KDP’s original merger thesis of dominating global beverage at large, essentially anything you could drink, hot or cold. That strategy, like 3G’s and Berkshire’s, was a failure for the same reasons.

Europe too

Nestlé, the world’s largest food company, has kept paring back too by launching a strategic review of its vitamins, minerals, and supplements business (including Nature’s Bounty) in order to refocus on its long-term pillars of pet care, coffee, and premium nutrition. Unilever is following the same script, having announced the spin-off of its entire ice cream division to sharpen its focus on beauty, personal care, and household products. These two giants, once symbols of diversification, are proving they are no different than their US peers… even at the very top of the food chain, the playbook is simplification, focus, and “bigger and fewer.”

Watered up

The water business has seen similar consolidation. Last summer, BlueTriton (the former Nestlé Waters North America) merged with Primo Water to create a North American hydration giant. A category once fragmented across dozens of regional players is now a scale-driven competitor, reflecting the same “bigger and fewer” logic that has defined every other corner of packaged food and beverage lately.

Yoplait can’t stay

General Mills made an equally decisive move. After years of struggling to grow yogurt, the company sold its US yogurt business to Lactalis in June 2025 and its Canadian yogurt operations to Sodiaal earlier in the year. In total, the divestitures amounted to $2.1 billion. General Mills is now concentrating its bets on categories like pet food and snacks, where growth and margins remain stronger.

Smuckered out

Smucker has also been reshaping itself in a way that underscores our same theme. In 2023, it sold a large portion of its mainstream pet food portfolio — including Rachael Ray Nutrish, Nature’s Recipe, 9Lives, Kibbles ’n Bits, and Gravy Train — to Post Holdings for $1.2 billion. What remains is a more focused set of higher-margin pet snacks and treats such as Milk-Bone and Meow Mix, alongside the transformative Hostess Brands acquisition that brought Twinkies and HoHos into the fold. The result is a leaner, sharper company concentrated on premium snacks, both for people and pets, rather than a sprawling mix of lower-growth or distracting brands.

Campbell Soup may be the next name to watch

The company already sits near the bottom of the sector’s long-term TSR charts, and late last year CEO Mark Clouse announced he would depart to become president of the Washington Redskins… an unusual (and pretty cool) exit that nevertheless left Campbell at a crossroads. Then, in June, Mary Alice Dorrance Malone passed away. She was the company’s largest individual shareholder and granddaughter of founder John T. Dorrance. Her death reopened memories of her family battles with activists in recent years determined to acquire or break up her grandfather’s company which the family has controlled so tightly for over 100 years. The company had already restructured significantly in recent years — selling its international businesses, divesting Bolthouse Farms, and acquiring Sovos Brands to bet on premium sauces and packaged meals. But whether these moves are enough to stave off renewed activist pressure — or to reposition Campbell amid the deconglomeration megatrend — remains to be seen.

Stock performance is everything

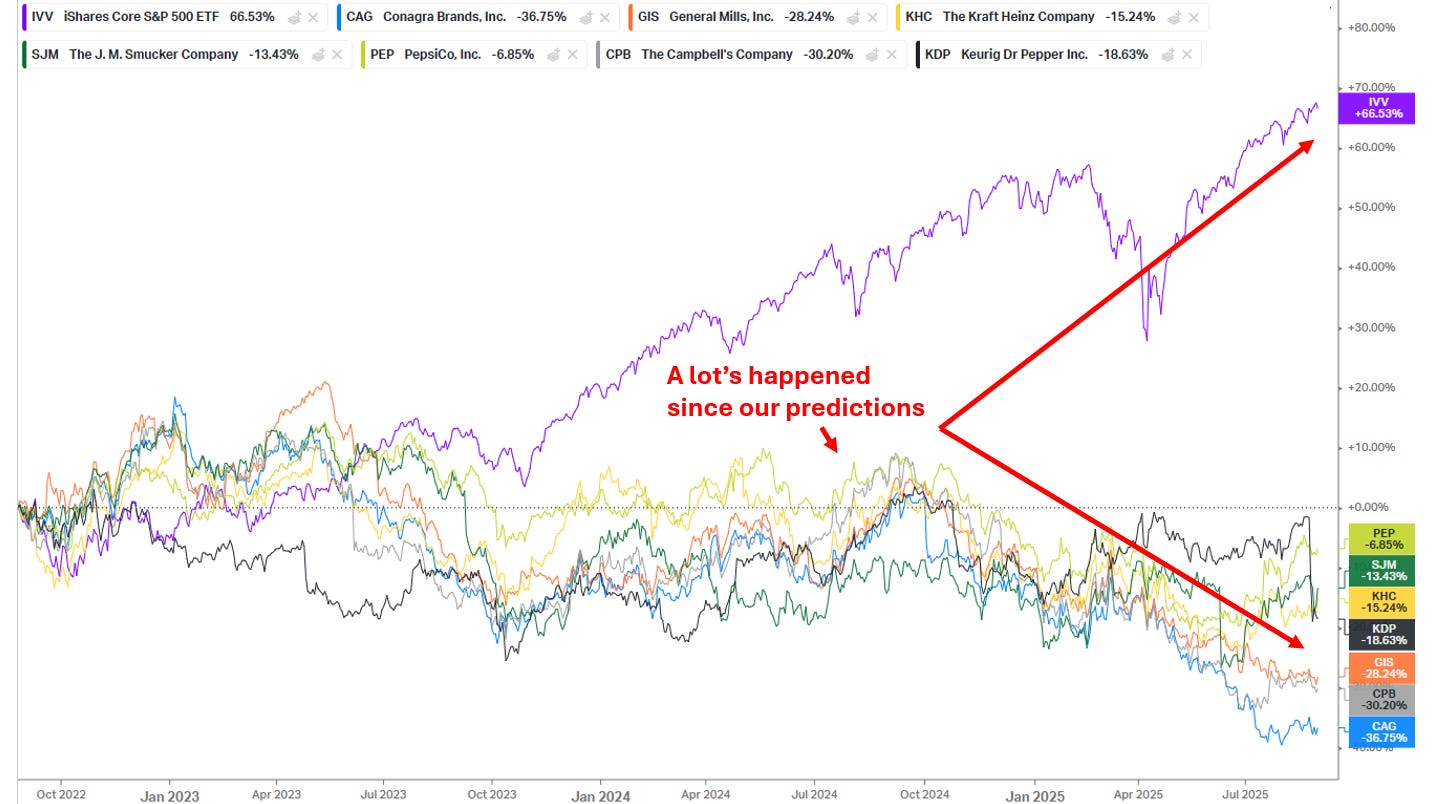

Taken together, these moves are not coincidences. They are the direct consequence of what we wrote one year ago — When TSRs deteriorate as they have (~80 to ~100 percentage point underperformances versus the S&P500 over the past 3 years) and multiples compress (NTM P/E ratios close to 20-year lows), boards are forced into difficult, structural, and often transformational decisions.

The conglomerates are breaking apart, the category champions are bulking up, and the “bigger and fewer” playbook is now the industry’s default setting.

You called the Mars-Kellanova deal almost exactly right, and the bigger theme about deconglomeration is playing out exacly as you predicted. What's interesting to me is how Kellanova as a standalone only existed for about a year befor getting acquired. The spin from Kellogg unlocked value imediately, but it also made Kellanova vulnerable. Mars saw an opportunity to scale up in snacks without the cereal baggage, and Kellanova shareholders got a solid premium. I'm curious whether more spin offs will follow this pattern, where the standalone period is just a brief pitstop before consolidation.